The friendship and rivalry between India's first two GMs - Vishy Anand and Dibyendu Barua

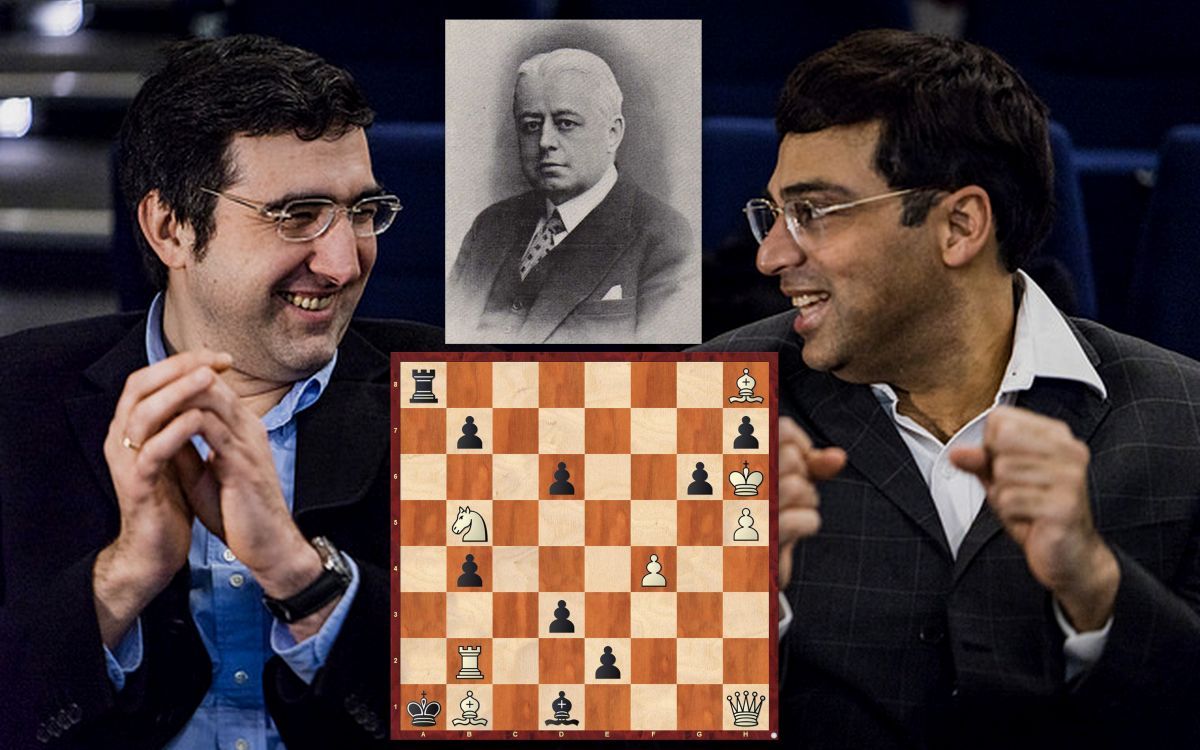

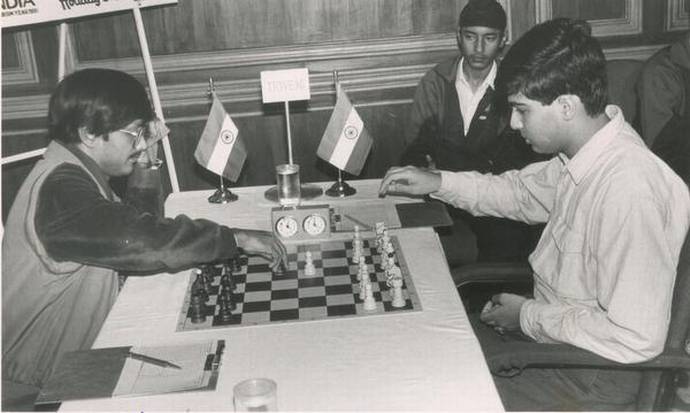

Back in the early 80s the biggest question on the mind of Indian chess fans was - Who would become India's first GM? There were many strong and senior players who were already IMs or close to IM strength and were attempting to break this barrier. But in came two youngsters - Vishy Anand born in 1969 and Dibyendu Barua born in 1966, who took the Indian chess by storm. Their rivalry was intense as they blitzed past all their competitors to become two of India's strongest chess players. In 1987 Vishy Anand ended the drought by becoming India's first GM. Four years later Barua achieved the feat in 1991. Anand and Barua were India's first two GMs. Deputy editor of Hindu Rakesh Rao sat down with both Anand and Barua together at the Taj Bengal, Kolkata and took them back down the memory lane to talk about their friendship, rivalry and more!

This article was first published in Sportstar and has been republished with their kind permission

Anand and Barua: The one and two play tango!

By Rakesh Rao

Dibyendu Barua and Viswanathan Anand — born three years apart, they were chess prodigies with awesome talent. When their paths clashed in the 1980s, they battled fiercely over the board. They were intense rivals in the race to become the country’s first grandmaster. Eventually, in 1987, Anand beat Barua by a distance to end India’s wait for its first GM. Barua was next in 1991. Many purists believe that Anand proved a more successful version of Barua while Barua ended up as a not-so-successful Anand.

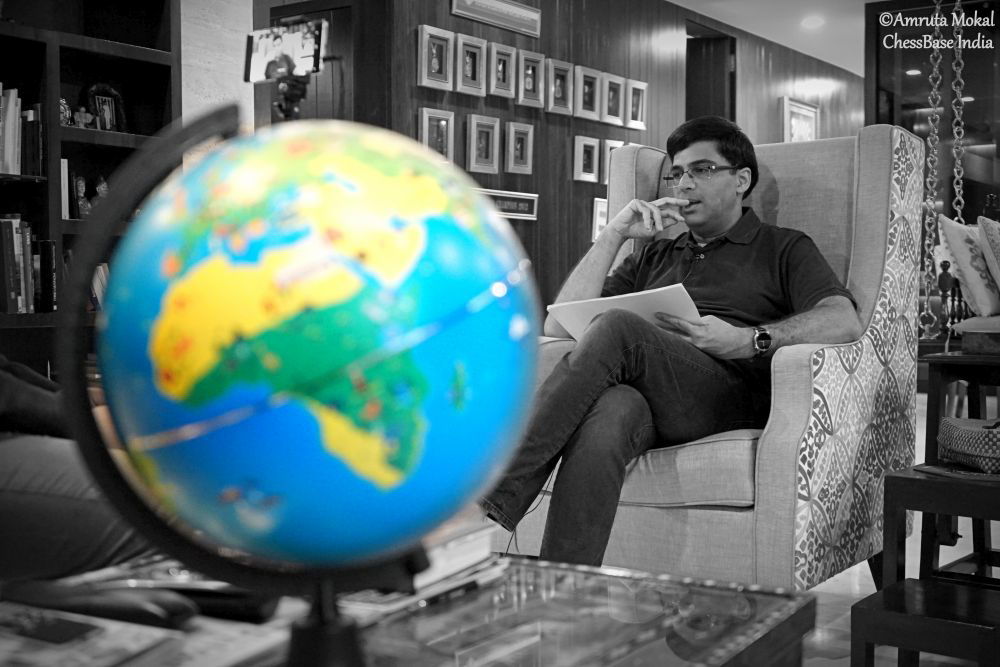

Though the two have not faced each other over the board since 1992, they share an amazing bond. It is not very often that one gets to catch them together. When Sportstar engaged them in a long chat, the two friends willingly looked at the era bygone, shared their memories of each other and more.

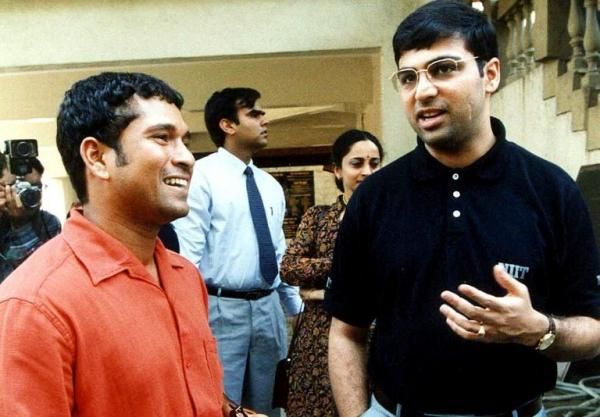

“First of all, we were rivals and colleagues for many years. We spent a lot of time together. You play in competitions. So I wouldn’t say we left aside our rivalry. That always co-existed with our friendship. But nowadays, whenever I am with him, I cannot resist the temptation to tease him. He cannot resist that same impulse.” These words from Anand about his good friend Dipu (as he refers to Dibyendu) give an insight into the man’s heart that cherishes old friendships. More so when he elaborates, “I can’t sit and suddenly become serious with him. It’s not how we were. I would say I get the same feeling sitting with Dipu that I get when I meet my old classmates.”

Barua is equally gracious and generous in praise when talking of Anand. “Now that’s Anand for you. He is so down to earth and so popular around the world. What chess is in India today, it’s due to Anand. I personally believe… there had to be a legend to show the path. He gave us the belief that we also could win… we could also win the world championship in spite of lacking facilities. Many feel that he benefited from staying in the Philippines for more than a year. Of course that helped him in the initial years, but to defeat all the top players single-handedly, and in all the formats. That’s no fluke.”

How do you remember your first impression of each other?

Anand: Seriously, in those days, in the junior circles, Dipu was already quite a legend. He was a ‘senior’ who was playing with the juniors just for a while. And he had already played a grandmaster (and beaten Viktor Korchnoi). So Dipu was already ahead, an international master, who had already played the national ‘A’ (championship) and was way above there.

Barua: The first time I saw him was in Delhi (national juniors). I remember the little boy wearing a cap. (Anand quickly explains: ‘I had a cap because (Arun) Vaidya used to spin his key chain during the games. So every time he swung his key chain, I would pull my cap over my eyes so that I didn’t have to see this key chain being spun around’). So I remember seeing little Anand, moving around the tournament hall. He hardly used to sit on the chair. He would make a move, go around the playing hall to see all the other games.

Anand: As I said, he was way above us. It was almost like Dipu was coming down to mingle with the masses. And in those days, a 16-year-old looked at a 17-year-old in awe. Generally, every year, you add one year and you could add 50 elo points. In our hierarchy, it was very skewed. I was not on top of most hierarchies because I was the youngest, 12... 13… or thereabouts when I first played. What I would consider a good result was beating two of these guys (pointing to Barua) and then losing to the third one. And I was very happy and so on.

Anand, do you recall any painful loss you suffered to Barua?

Anand (with mischief writ large on his face): In Gausdal (venue of the 1986 world junior championship), if he had not beaten me, I would have had some chances at first. When he beat me, I wanted to ask them (the organisers) to find his age certificate. And then erase this game. That was my only hope.

Barua: We were roommates in Gausdal and I remember, Anand was very upset with me, for 5-10 minutes…

Anand: I would still be upset. It was not that I enjoyed losing to anyone. There was some rivalry. It was not that we were best buddies, making draws all the time. We fought every game.

So when did you eventually overtake Barua?

Anand: Dipu was the national junior champion and I won my first national in March 1986. I remember, all of us were playing in Calcutta in the Tata Steel event and then went to Bombay. By this time, my rating was higher than his, consistently. (Anand’s recall was on the spot! When the rating for January 1986 was released, Anand (2405) led Barua (2395) for the first time. Since then, Anand has stayed ahead).

I remember the question making the rounds those days was, who would be India’s first GM — Anand or Barua?

Anand: Indeed, our biggest rivalry was for the GM title. We were playing all the Bhilwara events (in New Delhi) and some other events together. We were travelling. I remember going to Frunze, to Moscow once, so everyone was playing wherever they could to get a GM norm, get experience. We played the Lloyd Banks’ (tournament) together. I think, once I became a grandmaster (in December 1987) all sorts of doors opened for me and that was very nice.

Barua, how was Anand after he became a Grandmaster?

Barua: In the 1988 Thessaloniki Olympiad, which was my first Olympiad, I missed my first GM norm. In the final round, I had winning chances but I drew. So I was very upset. At this point, Anand, who was also my roommate, gave me a pat and said, ‘Dipu, don’t worry. You are pretty close to being a GM. You are already knocking on the door. You are almost there.’ And jokingly he added, ‘Let me enjoy being India’s only grandmaster for at least five years.’ And it almost happened. I became the second GM in 1991, four years after Anand became the first!

Did you give any advice to Barua when he kept missing GM norms?

Anand: I would have felt very uncomfortable giving advice. I knew what he needed to do. Generally, my memory of that impression now is that he simply did not study openings. He didn’t like to study. It was not that he was bad in openings. But he was not learning new openings. He was playing the same old openings and by sheer familiarity, knew them well. I don’t think I would have even dared to give him any advice. It would have been pretty presumptuous to do it.

Going back to chess in India in the 1980s, what is your memory of those days?

Anand: It was a world that we have already forgotten. You had to book a STD call (trunk call, as it was called then) to call each other (from outstation). There was no email. I mean, it was not that we met once in a while, but we even spoke once in a while. Nowadays, there are people I have met in 10 years but I am in regular touch with them.

It’s hard to remember those days. Those were still the days of Chess Informants in your suitcase. Sometimes, I’m very nostalgic for that era again when you could just play with a five-minute preparation. We used to trust our judgement. Nowadays we don’t trust our judgement. Now we always switch on the computer to see what I did wrong. But before, I would believe what I said and he would believe what he said and we would actually double-check and so on. It was a different era.

Everyone remembers their teenage years as different. Of course, from my perspective, the 1980s, were very innocent years. I don’t know how someone from a different generation would see that. Those were my innocent years and probably for him, as well.

Barua: Those days, before he became a GM, it was very difficult for us (other players) to make him sit and think (during a game). So during tournaments like Bhilwara and some others, players like Ravi Shekhar, Tiruchi N. Parameswaran and Praveen Thipsay would actually notice Anand thinking over the board and say, ‘Ah… Anand’s opponent has made him think...’ That was a big achievement for Anand’s rival to gain his respect. Even making Anand think over the board was something great. Nice days indeed.

As prodigies, did you two ever feel that the seniors of that time felt threatened, or did something unpleasant to stop you?

Anand: Rivalry always exists and when someone new is trying to come in, there is some resistance. I was too young then and oblivious to what was happening. I wouldn’t have recognised it even it was being done openly. And probably, it was not being done very openly. For the most part, not only would I not be aware of it happening even when it was brought to my attention, after a few days, I wouldn’t hold it on my chest. I was simply too young for that.

Now I look back, and sometimes think, that was not nice or so on. But by now, I have experienced both sides of the coin. I have experienced rivals coming in. I have watched them warily. There are all sorts of degrees. There is actually a time when you try and sabotage someone’s career. There are also times when you hope someone doesn’t do well. You start making plans and you prepare more for them. Everything from legitimate to immoral. Things span that spectrum. I think, now it’s a part of life and that’s how life is. Life is competition and that’s that.

Then, I think, I was too innocent to even notice. So very often, even if I had heard some story and that person spoke to me, I would speak to him. It was simply I could not carry any negative emotions. My parents kept me like that. And so it wasn’t a big deal then.

Today, as Barua also reinforced the fact that you were indeed a path-breaker for Indian chess, what is your take?

Anand: Well, first of all, lots of trends changed which benefited Indian chess. The whole computer revolution took off and we see its effect all over the world. Countries which played no part in chess before are now able to connect themselves and start playing and so on.

I feel, I was a catalyst for getting a lot of people introduced to the game in the first place. A lot of people might have heard of chess only because of me, because I was mentioned in the newspaper in that context. Perhaps, I brought chess to their attention, something like that. And that’s the impulse that you keep providing. Playing the game and people are motivated to give it a try. Some like it, some don’t and it goes like that. Participation started increasing. But India has also developed a lot of coaching structure. The federation has grown, the number of players in your city has grown and all that. Obviously, I can’t take credit for those things but I was an impulse, a catalyst whatever you want to call it.”

Finally, what was that one chess-playing quality that you admired in each other?

Anand: Dipu’s inventiveness… coping with anything. As I said, he didn’t study theory then. So very unconventional, he would almost always bring up something over the board.

Barua: Anand’s quick decision-making. Even before we could consider the possible options, he would have made his move.

Replay all the games between Anand and Barua

Vishy Anand and Dibyendu Barua have played against each other six times in the past. Their first game was in Kolkata 1986 and the last one was Kolkata 1992. Anand has 2 wins to Barua's 1 with three draws. Here are all the games for you to replay.

About the author

Rakesh Rao is a Deputy Editor of The Hindu and one of the leading sports journalists in India. From being a former Delhi chess player, he has covered a few World chess championships, Olympiads and Candidates events in the past three decades. He has also covered Olympic and Commonwealth games, F1, elite golf events on PGA Tour, European Tour, Asian Tour and several World and Continental events in several sports besides Test cricket, ODIs and T20 matches.